When I was 14, I went to the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Michigan. This is a story of a camp friendship, at a specific time, and a special place.

That was the summer of 1967: the Summer of Love in San Francisco, but in Detroit the summer of the 1967 (Rebellion), (Uprising), or (Riot)(—pick one). The Vietnam war intensified, against which public opinion was turning, and was first termed a "stalemate" (New York Times, by R. W. Apple, August 7). Martin Luther King, Jr. had declared "a time to break silence" about the War. These events were distant from pine woods between the lakes (Duck and Green), and music in the long summer evenings of the northwest lower peninsula of Michigan.

The National Music Camp (NMC) was was usually just called "Interlochen," then a woodsy crossroads with a state park and a camp store. (Now the Camp is simply termed the Interlochen Arts Camp to distinguish it from the Academy.) Joseph Maddy founded it in 1928. There were far fewer summer camps dedicated to music in 1967. NMC was distinctive, large, and long, a single 9-week session. Its prestige was bolstered by summer visitors such as Aaron Copland (1966), and annual visit by the boyishly handsome Van Cliburn who not only played but conducted. There are scores of notable former campers, in the arts and beyond. Well before 1967 it had become world class (and it still is).

For any 14-year-old, Interlochen was the real deal. I never would have applied without a teacher's earnest recommendation, because I never thought I could possibly be good enough to go there. My instrument was piano, so there was no shortage of competition for a limited number of places. My parents doubted I would be admitted and that they could afford the fees. I sent in an audition tape (reel-to-reel), knowing that a second tape might be requested, and was a few weeks later. Then thin letter arrived, a bad sign. But no!—not only was I admitted, but with a half-scholarship. My parents stretched to afford the rest, and with money left to me by my late grandfather, I had enough to accept admission.

Came Spring, came the deluge of mail: an introduction to the numerous rules and traditions. Lists of what to pack, what would be provided, and scores to choral music. Every camper studied in instrument, was in an ensemble, took theory, ear training, and an elective second instrument. Rather than one second instrument, I choose a class in which students got to play every orchestral instrument a little —not just once, but for several days. When I looked over the repertory list for my level of piano, my nerves rose; the choral music included Mendelssohn's Elijah: I began to be anxious: what had I gotten myself into? Did they really think I could do this?

Yet more mail: lots of rules. Boys' and Girls' camps were not only separated by the state highway, but were strictly off limits to each other. The whole camp was divided into zones by boundaries and those were clearly marked. Campers were strongly advised to sign up for the laundry service (I did). A swim test would be required if I wanted to take a canoe or sailboat out on Duck Lake. I had to sign the Camp Pledge (behavior, respect and commitment to artistic excellence), and then affirm it verbally my first day.

(Digression: Looking at the 2023 Camp Handbook, I'm struck by how little has changed as regards the basics, but how much more complicated life has become. We had no mobile phones, computers, drones, skateboards. I had Kodak Brownie camera (with film); I don't recall policies about substance abuse or weapons. There were definitely policies about "inappropriate intimacy," smoking, leaving your cabin at night, bullying, and misuse of the waterfront. The Camp Pledge is now twice as long. After 40 years of daytime life on a college campus, I hardly dare imagine all the challenges for the 2023 staff.)

Then there was the camp uniform. In 1967 we were told what to wear with no exceptions and little explanation. Now the handbook explains the idea: a tradition since 1928, the uniform represents unity, respect, a blurring of class distinctions, and membership in the Interlochen community. For boys in my day: blue corduroy pants, light blue shirts on weekdays, white on Sundays, always tucked in, with socks. Red sweaters or pullover red sweatshirts (except at performances). Girls wore Blue corduroy knickers and blue socks. Customization was limited to where you wore your camp badge: at the waist, or pants pocket, or on your shirt. (The badges tended to make holes in the shirt fabric, so pants were preferred.)

(Digression: In 2023 the uniform continues largely unchanged, but now boys can wear knickers as well. Wish I could have--I would have looked great in knickers, with long, thin legs. The Boys' camp east of the highway is now "Pines," girl's camps on the west side "Lakeside" and "Meadows." There are now cabins for nonbinary and transgender campers. I suspect they benefit greatly from the uniform: they can wear either and harmonize with everyone else. I'm so glad the world has changed in this regard. In 1967 that was beyond imagining.)

Came June, I finally arrived at camp—a four-hour drive north in those days. I was intimidated. I didn't even think of backing out, but my nerves and fears were at an all-time high. I was assigned cabin 3 with other 14- and 15-year olds and two counsellors, a "good cop" and "bad cop" (but the bad cap was not very bad, just a little stricter). Usually it all worked well. There were minor cabin disputes but I don't recall bullying or real conflict.

We filled our cabin, with barely enough room for bodies, bunks, clothes, and some musical instruments. Our cabin had special shelving for instrument cases—a small luxury; most did not. It also had recurrent problems with water pressure (each cabin had its own complete plumbing), and with 12 boys needing daily showers, that was a problem. Our counsellors had to beg shower space from other cabins; that's how I came to know the boys next door in Cabin 1. (Although arranged in rows under the pines, the cabins were not numbered in sequence, a scheme apparently invented by some chaotic woodland sprite.)

Living in such proximity, boys could not avoid getting to know other boys: who had allergies, and who belched or snored. (Lots of fart jokes, too.) After the first day I loved that life. The first night out came a chessboard—I quickly learned that this was a camp for talented smart kids and I had better keep up. For the first time I felt I was with true peers. Being smart, musical, and a reader was not considered odd but normal. Nicknames: mine was Ferbs, a nickname re-invented decades later for my sons. I was more stimulated and challenged than I had ever been. I forgot the trials of junior high school. It was better than I could have guessed.

I surprised myself by passing the swimming test, so I could use the boats: rowboats (ugh), canoes (OK), sailboats (one- or two-person Sailfishes--cool). The sailboats became my go-to on "forced fun" Friday afternoons. Interlochen had to mandate "fun" because otherwise many campers would practice at any available time something else was not scheduled.

Practice could happen anywhere in the woods, but usually in the practice huts --a long row of narrow practice rooms. The huts were always busy and finding one with a piano could become a chore (although pianists were supposed to have precedence to use those). Practice hours were supervised loosely, because little supervision was needed: student musicians were almost invariably on task, and they had good reason.

The atmosphere of understated but intense competition centered around the practice of challenges. The procedure basically sorted players in a band or orchestra section from first (best) to last (least) by campers voting which of two players performed a designated excerpt better by several criteria. Supposedly the voting was "blind" (everyone had their heads down and raised hands silently to vote). Talk about stress!—but modified in a peculiar way: the player next to you in the section was both a competitor and a key collaborator. Somehow, you had to get along. With a healthy dose of Midwestern "nice," it usually somehow worked. Hence the desire to practice almost all the time.

The challenge system under the right circumstances motivated less skilled players to become more skilled, to buckle down and really work. It worked best when the faculty section leader reminded players: "We admitted you to Interlochen because we know you can do it. So now you're responsible for showing us that you can." It worked with the right musicians, who practiced whenever possible. Others simply grew to accept a chair way down the section. For some, the system felt terrible. Everyone put up with it because that's the way it was.

(In the piano studio, our rankings were based partly on camper vote and partly on faculty evaluation. The motivating prize were performance opportunities for groups ranging in size from the studio to the whole camp.)

The point of all this was the music. The ensembles hooked me. I had never sung before in an 80-member choir with 18 other bass-baritones all of whom, like me, were receiving rigorous ear training. Our first big piece was Vaughan Williams' Toward the Unknown Region, a harmonically lush twelve minutes with full orchestra and organ. The impact of 80 voices was huge, but surpassed by the full orchestra: I had never heard or performed music anything like this. For me, the performance was transformative. I really began to grasp how powerful music can be.

In its best moments Interlochen taught me (a 14-year-old!): it's about the art, its not about me. We were there to learn to do something that connected us with an art far larger than most teenagers could imagine. The experience communicated one thing brilliantly: the music mattered. We were part of something big, summed up in the tradition of the "Interlochen theme" (by Howard Hanson) that closed every concert. It was always conducted by a student (usually the first violinist) Faculty and staff adults left the stage: it was played by campers, conducted by a camper. It pointed forward. Someday this art would be ours.

I was forced to get to know a lot of boys (and a few girls) who were from very different backgrounds and places. As an introvert, a reader and not a talker, this was difficult at first, but I learned. There were some international campers, and scholarship kids like me, and some apparently from wealthy families. Most had siblings (the baby boom). A few had gone to boarding school. For boys from California or the South the weather was usually too cold; for Swedish boy was always far too warm. A lot of boys were from metropolitan Detroit, Chicago, and New York. Almost all of us had nicknames --as I wrote, mine was "Ferbs" . Our knowledge of each other's real names was much hazier --those were on the camp badges, of course, and when counsellors passed out the mail. Otherwise we knew each other by our camp nicknames.

Eppy was a boy from Brooklyn. He played the bassoon, and he was pretty good. He had an off-beat sense of humor, goofy at times, and had a knack for quietly skirting or just barely complying with the rules. He lived in Cabin 1, the cabin where my Cabin 3 often went to shower because of a lack of water pressure. I saw him daily, but usually just casually. Like me, he was a scholarship boy.

Eppy and I were in different musical orbits and ensembles. By chance we wound up in the same theory class, and had the same homework. He chose piano as his second instrument, so we also had that in common. When it came time for me to try to play bassoon for my elective class, I came to appreciate how difficult his instrument was. I was awful, producing something like a very sick goose. Eppy was much better at piano than I was at bassoon.

Eppy and I signed up for one of the sailboats a number of times. A boat allowed some sense of freedom and getting away -- a welcome respite from all the rules and traditions. We both picked up the basic skills quickly, and learned how to tack into or across the wind. Eppy liked sailing on fresh water, no salt. (I had never been on or in salt water.) One late afternoon we had to be towed in from across the lake, because the wind had vanished as storm clouds approached. We weren't in any disciplinary trouble, though. Getting pulled in felt mildly humiliating, but other boys thought it was cool. Sailing those little boats conferred some kind of minor status.

I don't recall any specific conversations with Eppy, though we talked. His brother, a year or two younger, did not come to Interlochen. Like me, Eppy was an introvert, but once started could tell stories about life near the beach in Brooklyn, a life I had not imagined before. He took the subway by himself, saw an occasional city rat, had been to Carnegie Hall, and had seen Bernstein conduct. I was impressed, but tried not to show it. He was a city kid from part of New York, and I was from a farm town in Michigan. He did not put on a sophisticated attitude, so despite our differences we got a long pretty well. I don't recall ever talking about girls or sex with him. We were growing up in a more innocent time. Whatever happened in the 1960s, it hadn't happened yet to either of us.

After I got to know Eppy a little, I realized that he was very smart. He was a reader -he introduced me to Tolkien's saga in the old Ballantine edition. I figured out that he had progressed well beyond ninth grade, though only a few months older than I. He had a big vocabulary, but did not show off. He was very quick with numbers and number games, cards, and chess. As a smart kid, he felt he was an outsider, someone who didn't really belong in our age group, and I shared that feeling with him, though I was by no means so smart as he. We both felt gawky, sometimes out of place, and confused: in short, we were 14-year-old boys.

Eppy's parents visited early in the summer and brought him food from Brooklyn. He missed bagels, and they brought some, but by the time they got to Michigan they were pretty hard. Apparently his family was Jewish, something he had never mentioned --there were other Jewish boys in our cabins, but they all seemed very ordinary and uninterested in this detail. Like my parents visited for a weekend, when his arrived, they fussed over him, embarrassed him mildly, and then left. Unlike my parents, his seemed to feel that their son was in a very strange place very far away. I had no idea how different it must have seemed until I visited someone else in Brooklyn years later.

Though I knew Eppy pretty well --I did sail or otherwise hang around with other boys as well-- ours was strictly a camp friendship. I did not keep up with him after that summer, nor did it occur to me that I might have (though we were all given lists of campers' addresses --that seems incredible now). Eppy receded into my memory, and I do not recall ever thinking about him in succeeding decades.

Like everyone else, I became passingly familiar with the name Jeffrey Epstein in the media twenty years ago --something about a very rich guy in Florida and sex with minors. Later on, we all heard much more in lurid detail. I remember noticing that he had some connection with Interlochen, as well as big universities and Bill Clinton. At the time of his death in a New York prison in 2019, I recalled reading that he had been a amateur pianist. I still did not connect the dots --and in fairness, how many boys over the years have gone to Interlochen with last name of Epstein, Epworth, or something like that. Only in 2022, when I read a complicated story about a cello and an aspiring American concert artist, did I read the key detail that Jeffrey Epstein had attended Interlochen not as a pianist, but as a bassoonist.

By now dear reader has undoubtedly concluded by Eppy was no less than Jeffrey Epstein, the infamous and lurid sexual predator entangled with enormous wealth, rich a powerful people, and numerous criminal charges. With that New York Times article, it all clicked. I had always unthinkingly assumed that somehow Jeffrey Epstein was older than I, and at the National Music Camp sometime in the late 1960s. Wikipedia told me that he had been born in January 1953 (I in July), and was at Interlochen in 1967.

This knowledge was disconcerting at first, to say the least. I certainly never saw it coming, not that I gave the boy I knew as Eppy (or the man Jeffrey Epstein) any particular attention. I asked myself: what did I miss? What eluded me? In short: nothing. Eppy had a sly sense of humor, was very smart, and could subvert Interlochen's numerous rules without going too far. He did not seem mildly threatening, just mildly eccentric.

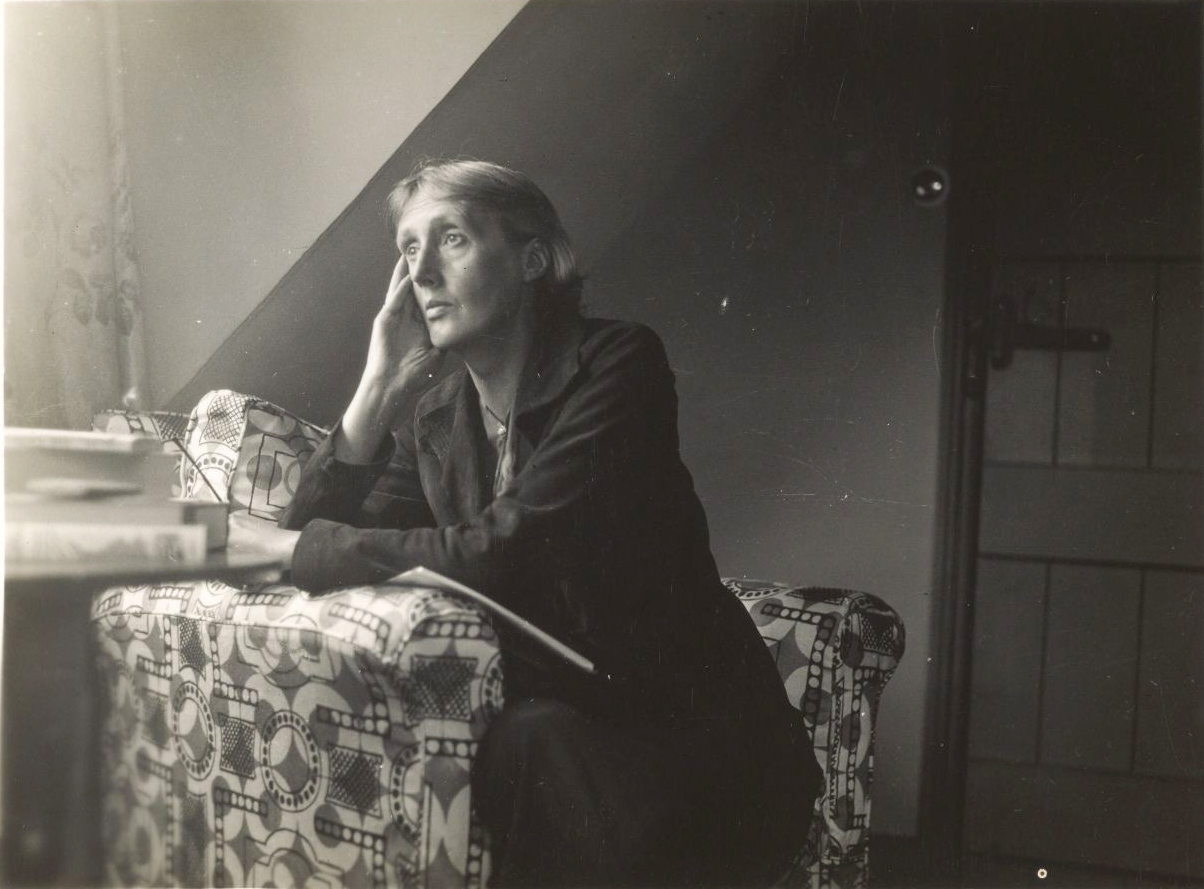

The camp photograph of his cabin --a standard pose--shows him (standing, at left) looking vaguely annoyed, hands in pockets, slightly out of the even line of boys, possibly not wearing socks, long sleeves rolled up. This photo was probably taken on Sunday, since the boys wearing white shirts. The others seem much more present in that moment. (Two counsellors are standing at right, and third from right.) There is nothing in my memory, or in this photograph, that imply the later Epstein's blazing financial trail, criminal acts, and sad end. He became a dangerous serial fabulist, noxious con artist, repeat offender, fundamentally fraudulent --but none of that could have been foretold from what I saw in 1967. I saw another mildly confused 14-year-old boy.

The journey from Eppy to Epstein is utterly mysterious to me. I cannot resolve it in any genuine or meaningful manner. It's a very sad story, and that statement in no way dismisses or diminishes the profound suffering of his victims.

I had an eerie sympathy with another New York Times story I read in 2023, around the tenth anniversary of the Boston Marathon terrorist bombing. The story told how impossible it has been for former friends and teachers of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (the younger brother of the two bombers) to reconcile the friendly guy they thought they knew with the terrorist he became. One of his friends, Youssef Eddafali, eventually wrote two letters to Tsarnaev: to "the old Jahar," whom he thought he knew, and another to "The Monster." Eddafali's own life was turned upside down by the bombing, by interrogation surveillance by the FBI, and it has been a long road back to anything resembling normal life for him. (He expected no reply to his letters, and has received none.) A researcher of mass shootings, Jaclyn Schildkraut, said that such experience “is like being knocked into a parallel universe . . . and you can’t get back.”

I have experienced a minor echo of that getting knocked into a parallel universe --a suddenly rewritten past. I can no longer remember my summer at Interlochen quite so innocently, though it remains overwhelming positive for me. Those memories now come with an important question mark: how did that happen? (--as well as other realizations about how various people were treated there in the 1960s, especially women). I do not believe, theologically or in any other way, that life had to turn out as it did for Eppy. At various points, he made his choices.

The summer at Interlochen that I found life-changing and -affirming was apparently insufficient for another boy, who eventually walked a long ways down a much darker path. I would like it all to make sense, and it does not, nor ever will.